CRAFT & LITERATURE

THE STITCHES THAT FREE US

By Maria Eliades

Embroidery sketch from Maria Eliades’ notebook.

Embroidery sketch from Maria Eliades’ notebook.

For over a decade, I’ve stitched and unstitched a novel. I learned a new language to write it, this story of Greeks living in Istanbul, Turkey in the 1950s and their descendents in 2010. But that’s not why it took me so long. I could claim the reason is because the material — a pogrom, intergenerational trauma — is difficult. I could claim the reason is perfectionism, which isn’t far from the truth. But if I’m being honest, it’s because of a classic diaspora trait: I am acting out of the fear that I won’t get it right.

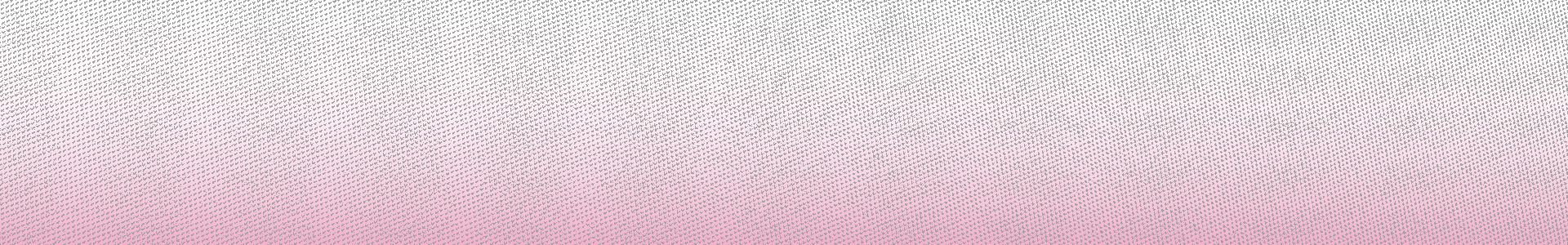

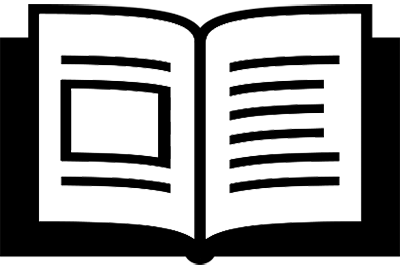

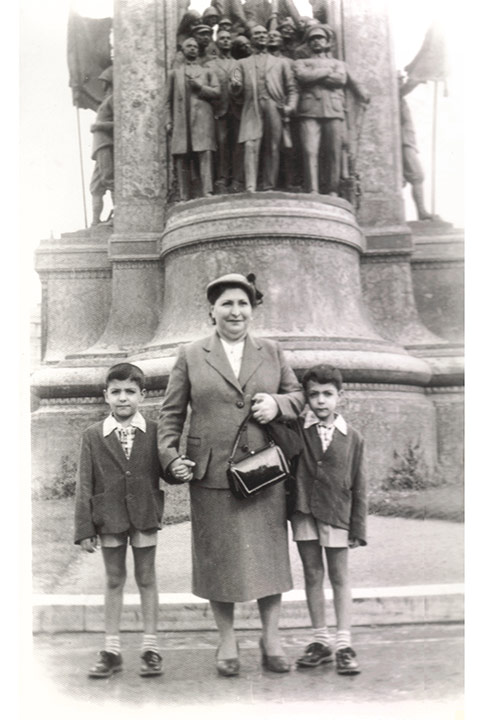

A photo of Maria Eliades’ father, grandmother, and uncle in 1959 in front of the Republic Monument that commemorates the formation of the Turkish Republic in Taksim Square. This was probably taken in 1959 before they left for the United States. Istanbul, Turkey.

Deciding to learn traditional Greek embroidery wouldn’t be what you’d think would be a cure for this malady, but on a blindingly bright summer morning in Athens, this is exactly what I set out to do.

I met my teacher, a textile artist and native Athenian, Loukia Richards, outside the Byzantine Museum. She proceeded to teach me about the continuum of symbols from archaic times to the 20th century, their evolution and the highly iconic and united environment of the Byzantine world, and that the context of the symbols was everything. She also encouraged me to think of the craft as something I could call my own. Most of all, she told me that what she did when she worked was to get the feeling of the motifs in her art.

"I became entranced by the idea of creating my own tavlion."

I paid attention. In my notebook, I scratched the curve of a leaf on a shoulder, the triangles and circles on a sleeve cuff, a boxy deer rearing its front legs on a wall hanging. I wasn't sure if I'd use any of it in my own design, but I drew it anyway. When we saw a replica of the mosaic of Justinian from Ravenna, I became entranced by the idea of creating my own tavlion, a talismanic embroidered patch that Byzantine emperors once awarded to soldiers in recognition of their service. But the more I sketched to fix it in a t-shirt design, the less it felt like what I needed to create.

The next day, I sketched a cypress tree, a woman holding a carnation, and a rooster together instinctively. The cypress was a symbol of fertility, as was the rooster. The carnation was a nod to both Turkish İznik pottery and Greek embroidery, as well as an offering of peace. When I started embroidering, I chose red for the woman's dress and decided the sleeve I had drawn was a scholar's robe – turning her into the infamous woman in red from the Gezi Park protests of 2013 that I had witnessed, her carnation a peace offering.

A woman sitting in the San Vitale Basilica, Ravenna, Italy, 2022. Photo: Maria Eliades.

A woman sitting in the San Vitale Basilica, Ravenna, Italy, 2022. Photo: Maria Eliades.

After my workshop with Loukia ended, I visited the Tzistarakis Mosque in Monastiraki, which had become an entry point to the Museum of Modern Greek Culture. The museum posed questions like, “What is the creation of modern Greeks and how does the historical identity of modern Greece manifest in them?”, and, my favorite, “What is modern Hellenism?”

Greek-Americans and most diaspora groups tend to think of identity as fixed. You either are or you aren't something, and the expression of what you are tends to be performative. It's in the visible cross, the dropping of Greek words in English. It's performing traditional dances the way we think our ancestors did, in costumes we think they wore. It's in being a practicing Greek Orthodox Christian.

Wedding photo of Maria Eliades’ paternal grandparents, Istanbul, Turkey, 1939.

We bind ourselves to repeating clothing and words and ideas out of a sense of duty, but it begins to feel like cosplay. The customs when performed perfectly are a monologue to be received by an audience, not a conversation. But what if we diaspora Greeks could allow ourselves to capture the feeling of the identity rather than sticking to preserving the past? Especially in this fraught moment in the U.S., where the very idea of who is American is being defined by its own performativity, what if we could allow ourselves to say, I have created my own version of my grandmother’s dish, and I’m proud of it.

I thought about this as I pulled out a drawer in the Museum of Modern Greek Culture. An embroidered headscarf and a photo of a family from Niğde, my paternal grandmother's birthplace, slid out. A recording wailed a winding song in Turkish and a voice said that the refugees* brought what they could hidden in their clothes, even in a rug.

Eventually those refugees created their own versions of traditions in other parts of Turkey, in Greece, and in the United States. These traditions have been carried on in people like me.

"Every generation of artists imitates at the start, but then creates off of what has come before to create something new"

I thought about this as I stitched my take on Greek traditional embroidery, and as I turned back to my novel. What if I could take what I had learned from Loukia to capture the feeling of the 1950s and of the life of the Greeks in Istanbul then, to unlock the stories I could tell about them?

Instead of slavishly recreating what few had documented, what if I allowed myself to give in to what fiction is: Stories that use something true, as Hemingway once said, to represent the truth? After all, every generation of artists imitates at the start, but then creates off of what has come before to create something new, in the feeling of the symbols and art forms that have come before us.

Maria Eliades. Photo: Emily Rand.

That is the embodiment of the traditions of what it means to be Greek: Not in “getting it right” in reproductions, but in carrying the essence of culture wherever we are in the world. We have a long history of doing just that in different parts of the world, after all. If we can do that now, staring into the face of the symbols that other Greeks have carried from mainland Greece, from the islands, and from Anatolia, we can embody Greekness in our own way. Not as stereotypes that we trap ourselves in, but as weavers of a new kind of cloth.

*Editor's note: The author refers to the Greek refugees from the Greek-Turkish war of 1922 and the following population exchange of 1923 mandated by the Treaty of Lausanne. An estimated 130,000 Greeks who were living in the Prefecture of Constantinople prior to 1918, and on the islands of Imvros and Tenedos, were exempted from this exchange.

Maria Eliades is an award-winning podcast host and producer, writer, and strategic communications professional. Her interests include politics, culture, art, literature, travel, and food in Turkey, Greece, and the United States. Her work has appeared in the Ploughshares blog, The Times Literary Supplement, The Puritan, PRI’s The World, EurasiaNet, and Time Out Istanbul. Born in New York, raised in New Jersey, she's lived in Turkey, the United Kingdom, and Greece, but she currently calls Washington, DC home. Maria holds a BA from Drew University and a MSt from the University of Oxford.

LINKS:

www.mariaeliades.com |

instagram: @mariainistanbul