THE ULM MODEL

HOW DESIGN ADVANCED DEMOCRACY IN GERMANY

Interview with Dr. Martin Mäntele, Head of HfG-Archive

Compact Appliance 'SK 4' (Radio-Phono-Combination) also know as 'Snow White's Coffin', 1956. Design by Hans Gugelot in collaboration with Dieter Rams (Braun AG), manufactured by Braun AG. Photo: Oleg Kuchar © HfG-Archiv / Museum Ulm.

Compact Appliance 'SK 4' (Radio-Phono-Combination) also know as 'Snow White's Coffin', 1956. Design by Hans Gugelot in collaboration with Dieter Rams (Braun AG), manufactured by Braun AG. Photo: Oleg Kuchar © HfG-Archiv / Museum Ulm.

Like its pre-war predecessor Bauhaus, Ulm School of Design (HfG in Ulm) was short-lived. Nevertheless, Ulm School of Design had a great influence on German and international post-war design such as Braun and Lufthansa. SMCK Magazine interviewed Dr. Mäntele on the amazing contribution of the Ulm model to Germany's democratization and public image.

The political motivation of the donors – who included U.S. High Commissioner for Germany John J. McCloy, the sister of two emblematic resistance fighters Inge Scholl, and the Norwegian Refugee Council – was to help the younger generation understand and acknowledge the new democratic system finally established in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Indeed, McCloy spoke of the ‘advancement of democratic life’ in Germany that the school should provide. Most of the students were teenagers in the 1930s and 1940s, and many had served in the war.

'Transparency', 1953. Collage on paper. Lecturer: Walter Peterhans, student: Ingela Albers.

Photo: Oleg Kuchar © HfG-Archiv / Museum Ulm.

The school was also a way to commemorate the actions of Hans and Sophie Scholl and the resistance circle of the White Rose. They intended to establish a school based on the ideas of the new democratic system and to educate the young generation about these new ideals. The curriculum was devised to help students become independent-thinking human beings who would not be as easily misled and manipulated by propaganda and lies as the generation before them.

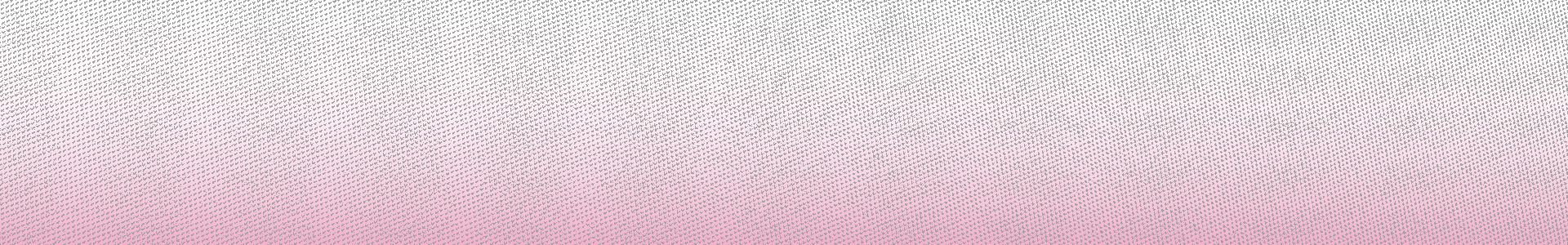

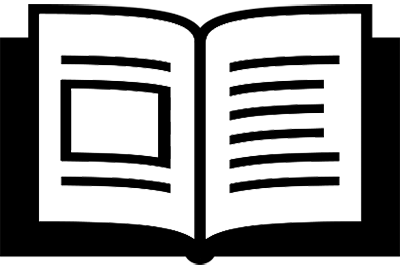

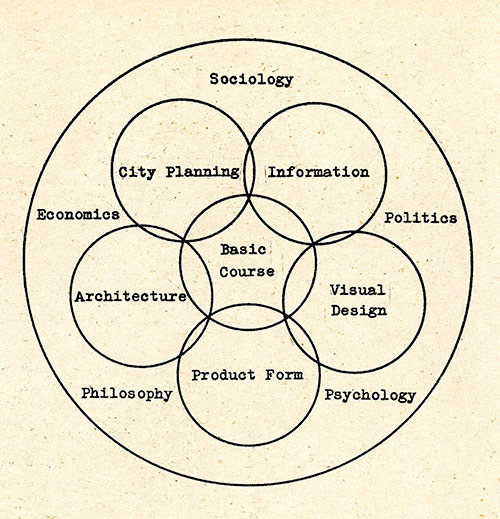

The basic idea was to establish industrial design as a scientific discipline rather than an artistic practice. The school created what eventually was called the ‘Ulm Model,’ defined by Otl Aicher as a concept of design based on technology and science: the designer, he claimed, was no longer “a lofty artist.” Tomás Maldonado expressed the school’s aim more directly: “The designer will be the coordinator…His will be the final responsibility for maximum productivity in fabrication, and for maximum material and cultural consumer satisfaction.”

Street Lighting System, 1965/66. Department for Product Design, lecturer: Walter Zeischegg. Students: P. Hofmeister, T. Mentzel, W. Zemp. © HfG-Archiv / Museum Ulm. Photo: Ernst Fesseler, Bad Waldsee.

Street Lighting System, 1965/66. Department for Product Design, lecturer: Walter Zeischegg. Students: P. Hofmeister, T. Mentzel, W. Zemp. © HfG-Archiv / Museum Ulm. Photo: Ernst Fesseler, Bad Waldsee.

The Ulm Model

The concept of the Ulm Model that the designer must research and gather data to inform the final design and thus adapt his aesthetic concept to the necessities of production processes and the market is still valid today – although many might not know the origin of this method. We should mention Gui Bonsiepe, certainly was one of the most prolific promoters of the Ulm School of Design, editing and writing so many articles for the school's journal, Ulm (21 editions from 1958 to 1968).

Educational Program for the Ulm School of Design devised by Inge Scholl, Otl Aicher, and Max Bill, 1950–53. Design: Otl Aicher. Hectography by © HfG-Archiv / Museum Ulm.

In its initial conception and first years of teaching, the idea prevailed that the HfG Ulm would be a second Bauhaus. The name derives from the second part of the title Staatliches Bauhaus Dessau, Hochschule für Gestaltung.

The selection of lecturers like Walter Peterhans, Josef Albers, Helene Nonné-Schmidt, and – for one week only – Johannes Itten shows this intention. However, already within this circle of former Bauhäusler (as they are called in German) we can find very divergent ideas about what should be taught at a design school. The so-called Grundlehre is the one element where the ideas of the Bauhaus pedagogy can most easily be traced in the Ulm curriculum. Yet, already in the late 1950s, the Bauhaus was renounced as a blueprint for the school.

The beauty of humble materials

At first Max Bill, HfG rector, estimated the total cost for all the buildings on the campus, including the main building, three student halls, and houses for the lecturers at around two million Deutschmarks. This is the sum that Inge Scholl managed to raise, with one million Deutschmarks from the U.S.-financed reeducation fund alone.

When Bill finalized his plans in the winter of 1952, he admitted to Scholl that they were short “the third million.” After the initial shock had worn off, they began thinking about how to compensate for this deficit.

'Ulm stool' designed by Max Bill. Reedition of the item used at HfG Ulm. Photo: Christos Vittoratos / Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0) modified.

One result is the now famous Ulm stool, a very simple seat produced in the school’s wood workshop because there was no money to buy chairs. In a way, one could say that Bill tried to highlight the aesthetic qualities, if not beauty, of these humble materials like pure concrete, white-washed brick walls, or inexpensive wood paneling.

This is certainly a lesson we could still apply today. My favorite example is the terrazzo floor on the second story. Terrazzo can be laid out without any joints. But Bill picked up the measurement of his grid for the building and thus transformed the floor in that room (and also outside, on the terrace) into a very intriguing pattern.

Bauhaus versus HFG Ulm

In 1919, Walter Gropius wrote in his Bauhaus manifesto that the building should be the ultimate goal of all artistic endeavors. In 1955, during his inaugural speech at the opening of the HfG Building, Max Bill said that everything, from spoon to city, is to be designed – meaning that all things around us need to be designed. This seems to be a similar approach. The main difference is that the HfG is truly dedicated to industrial design whereas the Bauhaus was still applying many more arts- and crafts-oriented methods. There were designs and methods aimed at industrial production, but which still needed a lot of manual work during production, like Theodor Bogler's ceramics or Wilhelm Wagenfeld's iconic table lamp.

Stackable Tableware 'TC 100', 1959. Department for Product Design. Diploma Work: Hans (Nick) Roericht

Manufacturer: Thomas/Rosenthal AG, Waldershof. Industrial china. © HfG-Archiv / Museum Ulm.

Photo: Ernst Fesseler, Bad Waldsee.

Stackable Tableware 'TC 100', 1959. Department for Product Design. Diploma Work: Hans (Nick) Roericht

Manufacturer: Thomas/Rosenthal AG, Waldershof. Industrial china. © HfG-Archiv / Museum Ulm.

Photo: Ernst Fesseler, Bad Waldsee.

LINKS:

hfg-archiv.museumulm.de |

instagram: @hfg.archiv.ulm