RUGS ARE GUARDIANS OF MEMORY, SILENT WITNESSES OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE

WEAVING IS AN IMPORTANT PART OF ARMENIAN CULTURE.

Interview by Loukia Richards

Armenian Kazak double niche Prayer rug, 1912. The Hand (Khamsa), particularly the open right hand, is a sign of protection that also represents blessings, power and strength, and is seen as potent in deflecting the evil eye for all peoples of the Middle East, Muslims, Christians and Jews alike. Photo: A. Tavukciyan.

Armenian Kazak double niche Prayer rug, 1912. The Hand (Khamsa), particularly the open right hand, is a sign of protection that also represents blessings, power and strength, and is seen as potent in deflecting the evil eye for all peoples of the Middle East, Muslims, Christians and Jews alike. Photo: A. Tavukciyan.

Many beautiful designs of Oriental rugs are reproductions of Christian and Armenian symbols and concepts, says expert and collector Arto Tavukciyan. In the interview, he describes how rugs can reveal the truth about stolen cultural heritage and restore the identity of a nation destroyed by ethnic cleansing.

SMCK: How did you come to work with antique rugs and what types of objects do you handle in your business, Hye Antiques?

ARTO TAVUKCIYAN: I was born in Montreal to an Armenian family from Istanbul. My parents left after the Istanbul Pogroms in 1955 when Christian businesses and churches were attacked. My wife and I moved to Vancouver in 1992. I worked as Art Director for several ad agencies, including McCann-Erickson. I was also the founding art director of NUVO magazine.

Eventually I realized that clients prefer to work with younger people. I was always interested in antique rugs, though I hadn't yet figured out why. Aesthetically I was drawn to Caucasian rugs, especially Kazakh, because of their bold geometric patterns and striking colors.

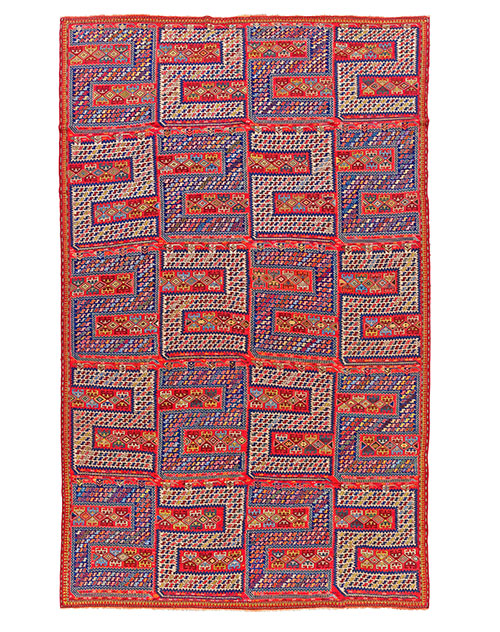

Antique Artsakh Armenian rug (Nagorno Karabagh), late 19th century. Photo: A. Tavukciyan.

As I began to research antique rugs, I learned that Armenians had woven many of these Caucasian rugs. As I dug further, I discovered that Armenians were among the earliest weavers in history and weaving was an important part of our ancient culture.

I discovered that Armenians wove the majority of Kazak and Nagorno-Karabakh rugs, many Eastern Caucasian rugs, and also the majority in Eastern Anatolia – what is today eastern Turkey. The area, which begins just east of Cappadocia, comprises along with present-day Armenia, the geographic region known as the Armenian highlands.

Most importantly I found that the accepted theory that the original weavers were the Turkic nomads who migrated to Anatolia in the twelfth century and conquered Anatolia was false. There is documented proof of weaving in Anatolia thousands of years before the appearance of the Turkic tribes. Also, the belief that Turkic motifs imported from Central Asia were what was reflected in Antique Caucasian and Anatolian rugs was also wrong. In reality these were ancient Anatolian motifs dating from petroglyphs to their use by the Anatolian sedentary cultures of the Hittites, Luwians, Lydians, Phrygians, Assyrians, Urartians, Byzantines, and finally the Armenians that was reflected in the rugs. You can see many of these motifs in the remaining Byzantine and Armenian medieval churches, manuscripts, and Armenian Khachkars (cross stones).

SMCK: What is an "antique" rug?

ARTO TAVUKCIYAN: A rug is considered antique after 100 years and a semi-antique when between 50 and 100 years old. Antique rugs and kilims are more desirable than new rugs because of the better workmanship and dyes. Natural flowers and plants were used to create them. The dye-maker was as important in the rug-making process as the designer and the weaver. Natural dyes were more beautiful and the overall colors more harmonious than the synthetic dyes of today. In addition to the workshops, villagers wove rugs for their own personal use. These rugs reflect their ancient traditions and beliefs.

Armenian Village Kazak rug, 1840. Depicted on the bottom right is a köçek male dancer. The köçek was typically a very handsome young male slave rakkas, or dancer, recruited usually from among the ranks of the non-Muslim subject nations of the empire who cross-dressed in feminine attire, and was employed as an entertainer for wedding or circumcision celebrations, feasts and festivals. The custom was outlawed in 1857 by the Sultan due to homosexual exploitation. Photo: A. Tavukciyan.

Armenian Village Kazak rug, 1840. Depicted on the bottom right is a köçek male dancer. The köçek was typically a very handsome young male slave rakkas, or dancer, recruited usually from among the ranks of the non-Muslim subject nations of the empire who cross-dressed in feminine attire, and was employed as an entertainer for wedding or circumcision celebrations, feasts and festivals. The custom was outlawed in 1857 by the Sultan due to homosexual exploitation. Photo: A. Tavukciyan.

Those informal village rugs are the ones that really speak to me, as well as the rugs woven as gifts to churches to honor departed loved ones or rugs woven as wedding gifts or for some other commemoration. Today's designs are a derivative of those motifs, losing their pure essence.

Rugs were passed on or sold from one person to another over the course of their history. Provenance is hard to track beyond one or two owners. The looting of churches and homes from the first Seljuk invasions to the Genocide in 1915 adds another dimension of confusion.

SMCK: What is the difference between a rug and a kilim?

ARTO TAVUKCIYAN: Both carpets and rugs are piled. An individual knot is woven one at a time, in a particular color on a template grid to make a larger design. It's similar to a mosaic where each individual tiny mosaic is part of a larger design. A carpet is generally larger than 10 feet long and 8 feet wide and rugs are smaller.

A kilim is a flat woven textile. It is made by interweaving the warp (vertical yarns) and wefts (horizontal yarns) on looms.

Large Antique Armenian Kilim, circa 1900. The repeated motifs are "facing serpents" not animal talons or "Dyrnaks" as most rug enthusiasts believe. Photo: A. Tavukciyan.

SMCK: Many people do not know about the tragedy of the Armenian people or the genocides between 1890-1915. The objects you work with can also be seen as guardians of memory and silent witnesses of the crimes against the Armenian people.

ARTO TAVUKCIYAN: Rugs as guardians of memory and silent witnesses of the crimes against the Armenian people is a very apt expression.

Since 1915, Turks and Azeris have made a concerted effort to exclude Armenians from the weaving culture of Anatolia and the Caucasus. The reason is political. They claim Armenians never wove rugs and were only merchants. Their intent is to separate Armenians from the weaving culture of the region thus providing an argument against the Armenian presence in the region. By separating Armenians from the region's culture their argument is Armenians were never there or were interlopers. Armenians are indigenous to the region and have a history of at least 2,500 years in Anatolia and the Caucasus.

Most believe that only Muslims use prayer rugs or that the Mihrab or prayer niche's origin is Islamic. This is untrue. Eastern Christians like the Armenians and Assyrians used prayer rugs in churches. There are monuments in Anatolia from ancient cultures and carvings from Christian Assyrians of prayer niches well before the advent of Islam.

For Armenians, prostrating and kissing the earth on a rug during prayer is registered in the Armenian language. The word "worship" in Armenian literally means to kiss the earth. There is no other language to my knowledge that has a word that expresses or describes the act of worship so literally, which is proof the practice was used before the advent of Islam. Not just prostration, which is a practice older than Christianity, but literally "kissing the earth."

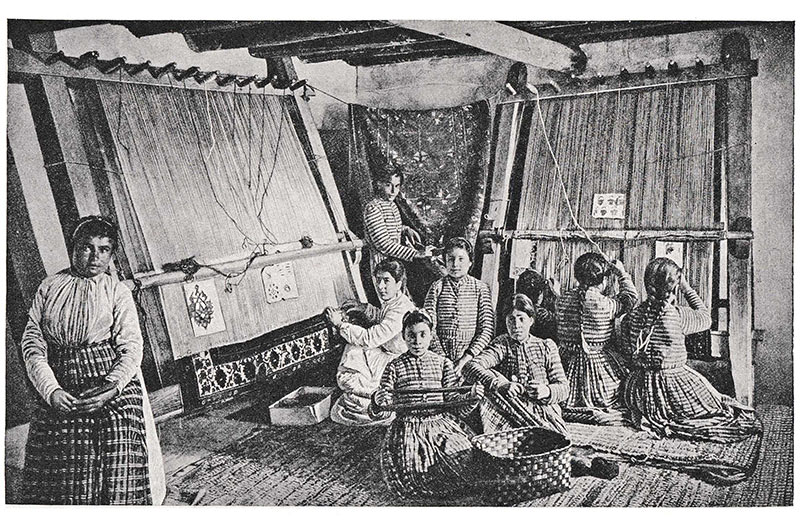

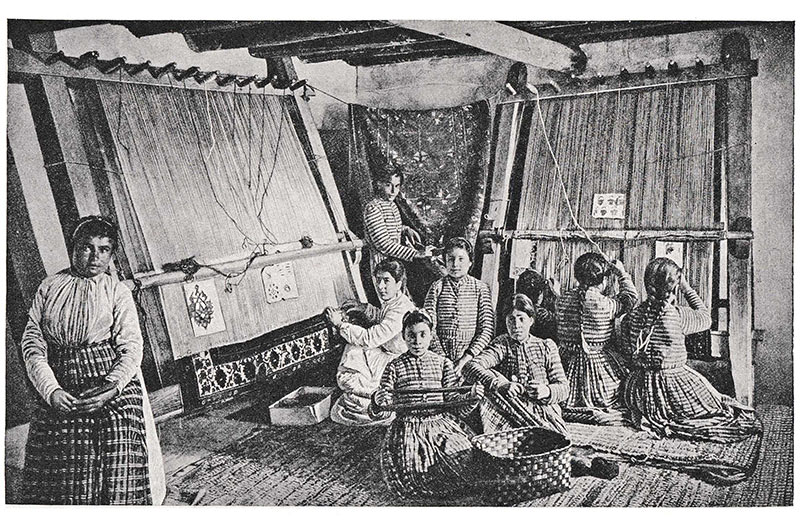

Armenian carpet manufactory in Eastern Kurdistan. Photo: Early Twentieth Century Anthropology.

"As craftsmen the Armenians show considerable capacity. They have been long renowned for their skill and artistry in carpet-making. Most of the carpets known as Turkish are manufactured by them and sold to the Western world by merchants and traders in Constantinople". Noel Buxton in Peoples of All Nations Their Life Today and Story of Their Past.

Armenian carpet manufactory in Eastern Kurdistan. Photo: Early Twentieth Century Anthropology.

"As craftsmen the Armenians show considerable capacity. They have been long renowned for their skill and artistry in carpet-making. Most of the carpets known as Turkish are manufactured by them and sold to the Western world by merchants and traders in Constantinople". Noel Buxton in Peoples of All Nations Their Life Today and Story of Their Past.

In the Ottoman era, as a result of Turkification and Islamization of Armenians and other Christians, people started to hide their Christian identity to avoid discrimination and persecution. So the practice of kneeling on rugs and kissing the earth during prayer disappeared and with it the art of Armenian prayer rugs. Nowadays surviving Armenian prayer rugs are wrongly labeled Islamic or Turkish.

There are many common misunderstandings about rug motifs, many coined by Europeans without understanding their true significance. I sometimes wonder whether this was ignorance or intentional.

To put things in context, I have to first state that the Western world today suffers from oikophobia, or fear of home. Almost everyone is familiar with the phenomenon of people who blame their own country or civilization for everything, who feel embarrassed about their own culture. Oikophobia is an extreme aversion to the sacred, and the thwarting of the connection of the sacred to the culture of the West.

Phrygian Midas Monument, Yazılıkaya village, Han - Eskişehir, Turkey. This Phrygian relief is 17 meters high and dates from the 6th century BC. It's an early example of the Mihrab/Niche motif which predates Christianity and Islam. Photo: Zeynel Cebeci (Wikimedia Commons).

Phrygian Midas Monument, Yazılıkaya village, Han - Eskişehir, Turkey. This Phrygian relief is 17 meters high and dates from the 6th century BC. It's an early example of the Mihrab/Niche motif which predates Christianity and Islam. Photo: Zeynel Cebeci (Wikimedia Commons).

SMCK: The Armenian genocide has been recognized by thirty-four countries, but not by Turkey, Pakistan, or Azerbaijan. Turkey attributes the mass deaths of the Ottoman Empire's Armenian subjects to the harsh conditions of the first world war and denies the claim that the mass murders were centrally planned and executed. What do Armenian rugs tell us today about memory, genocide, and cultural expropriation?

ARTO TAVUKCIYAN: F. R. Martin, a well-known Swedish rug scholar in England in the nineteenth century wrote A History of Oriental Rugs Before 1800 fully acknowledging the seminal contributions of the Armenians to the art of weaving, especially in the creation of the famous Dragon rugs from Nagorno-Karabakh. According to many Western historians and architects, medieval and early post-medieval European architecture can trace its origins to Armenia, which was the birthplace of Romanesque and Gothic architectural styles later adopted and spread throughout Europe.

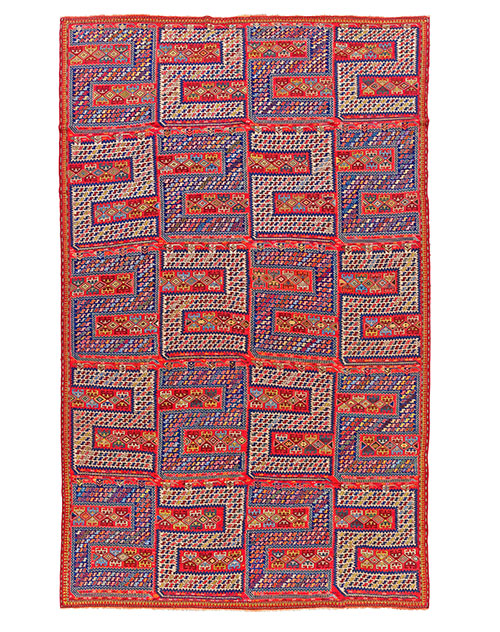

Armenian Dragon Sileh, 2nd half of 19th century. This 'Sileh' carpet is woven using the weft-wrapping technique known as soumakh, with a design of large S-shaped motifs that represent highly stylized, mythological dragons. Dragon mythology has been a part of Armenian culture since time immemorial. Photo: A. Tavukciyan.

But after the Armenian Genocide in 1915 – when Armenians were ethnically-cleansed from their Anatolian homeland, churches were destroyed, village names were changed, and art and culture was appropriated – the Turkish government begun to deny the extermination of the Armenians. Unfortunately the Western powers, in their desire to keep the new Turkish republic in the fold as a bulwark against the Soviets, closed their eyes to the atrocities and the cultural theft.

Reeling from mass extermination and subsequent wars, Armenians were too shell-shocked and devastated to protest even as their cultural legacy was being stolen in front of their eyes. Their first priority was survival. Also, Armenia being pulled behind the Iron Curtain as a new Soviet state in 1921 did not help.

It wasn't until the 1970s that a group of Armenian diasporan rug merchants in the United States began to fight back by founding the Armenian Rug Society and organizing rug seminars and exhibitions with Armenian inscribed rugs. Today, due to the commitment of collectors, experts, and the Armenian Rugs Society, Armenians' seminal place in rug history is slowly being restored.

Two special features of Armenian rugs

• Armenian rugs have bold primary colors.

Red and blue were the most common colors. Red is commonly used as a background color. Armenian national garments and rugs are often adorned with a deep, saturated red. This comes from a tiny insect called the Armenian cochineal (Porphyrophora hamelii), also known as "Kermes," which is indigenous to the Ararat plain and Aras River valley in the Armenian highlands.

• Armenian rugs are geometric and abstract.

Armenian rugs can be described as Totemic or Monumental. They are not representational or decorative like Persian or Azeri rugs. Rugs like the Sevan design are based on floor plans of medieval churches; crosses and cruciform shapes are used often. Antique Armenian rugs always convey a meaning.

Armenian Karabagh Prayer rug (detail) dated 1881. Armenians along with other Eastern Christians used Prayer rugs in Church to kneel on and pray towards the Alter. The cavernous medieval churches were cold in winter. Originally there were no pews so people sat or knelt on rugs to keep warm. Also, rugs were used as curtains to cover or separate the Ciborium from the public. Photo: A. Tavukciyan.

Armenian Karabagh Prayer rug (detail) dated 1881. Armenians along with other Eastern Christians used Prayer rugs in Church to kneel on and pray towards the Alter. The cavernous medieval churches were cold in winter. Originally there were no pews so people sat or knelt on rugs to keep warm. Also, rugs were used as curtains to cover or separate the Ciborium from the public. Photo: A. Tavukciyan.

LINKS:

www.hyeantiques.com

|

instagram: hye_antiques |

facebook: Hyeantiques