ART HAS NO VALUE

FINDING THE PRICE OF ART IS A REAL CHALLENGE!

By Loukia Richards

Gucci Shoes in a display window. Photo: Chr. Ziegler.

Gucci Shoes in a display window. Photo: Chr. Ziegler.

What would be more valuable to you if you lived in the jungle: a Swiss army knife or a Picasso painting hanging in your hut?

It is relatively simple to calculate the value of a pair of shoes – a common item and basic need in most societies. You add up the cost of the materials, design, shoemaker's wages, electricity and other overhead including the cost of the initial investment for purchasing tools, machinery, and equipment, as well as depreciation, and you arrive at a figure that represents the item's material value. Let's say ten euros.

But that's not the price you charge for the shoes, just what it costs you to make them. Your selling price is determined by additional factors. For example: do you sell retail or wholesale? To make our point easier to understand, let's say that you sell directly to retail customers.

To the cost of the materials and manufacturing, you must then add the costs of rent and utilities for the retail space, the salesperson's wage, advertising, transport from workshop to store, and so on to arrive at the sum needed per unit sold to be 'invested' in new materials to keep production going, your pension/insurance fees and taxes, plus VAT, accounting fees, the cost of design and marketing workshops that helped you to develop an exclusive product or a marketing plan and, of course, your profit – the amount of money that does not correspond to past spending, but is a projection of future liquidity.

You may also include in your retail price the added value of your reputation or how much it has cost you over the years to become famous for your designs and quality, as well as your desirability as a fashion brand. The beauty or exclusivity of your product, the scarcity of materials used, as well as the presence or absence of other competitors of equal quality and standing in your sector are also factors that influence the retail price of the pair of shoes you produced.

Having taken all these costs into account, you may arrive at a retail price that is two, three, ten, one hundred, or more times the initial material value of ten euros.

Shoes are a simple example because even if handmade and thus unique in a sense, making them follows a standard process that can be repeated infinite times with the same results. Thus, the human effort, skills, and time invested in making a pair of shoes can also be calculated.

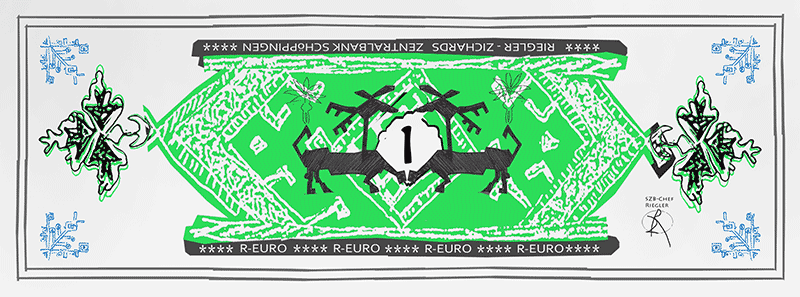

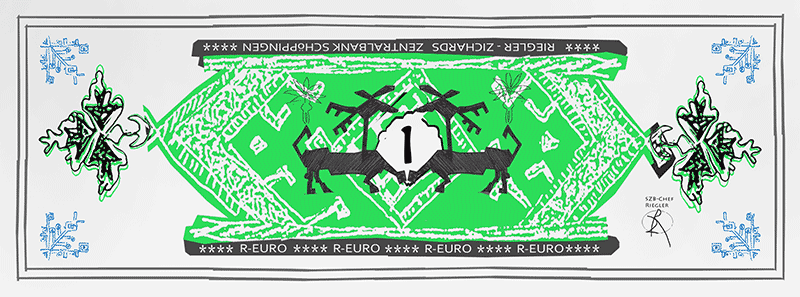

"One Reuro". Self-made paper bank note. Photo: Chr. Ziegler.

"One Reuro". Self-made paper bank note. Photo: Chr. Ziegler.

Human Needs

All products or services that cover human needs, basic and even some wants, such as clothing, food, energy, housing, transport, education, medical care, child-minding services and so on are valuable.

Your family, partners, and friends may have good reasons to be proud of you for your artistic achievements and efforts, for your talents and commitment, however, many excellent artists never manage to earn a living from selling their work regularly. Artistic merit does not necessarily define the artist's price.

The economic and monetary value of art is difficult, if not impossible, to calculate. Consumers do not starve or freeze or are unable to travel or cannot read or write if they do not find art to buy. Nor can artists calculate how long it will take them to develop an idea or how long it will take to implement this idea in material or digital form or how long it will take them to market this idea. Thus, it is very difficult to talk about 'producing art' in the same way we talk about producing a pair of good shoes. We cannot find the 'value' of the process.

Public Consent

Gold, silver, diamonds are rare and hard to mine, one may argue, and not necessarily needed for survival, even if precious metals have medicinal properties as well. Since antiquity precious metals have functioned as tokens for accumulating wealth and acquiring goods and property. Why can we not apply the same principle to art?

To do so, we need public consensus. People must agree on what art is valuable to store and exchange as they did with the metals and stones which they also invested with ideas of power, beauty, spirituality, and immortality.

Nowadays, we trust in the value of money – paper and digital – to buy us food, housing, clothing, transport, and services. We accept a number written on a banknote or appearing on the credit card reader as real, even if ‘bank runs’ occasionally prove that credit (from the Latin credo, to believe, have faith in) is based on trust.

There is still a lot to be done until we reach the point that a bank will accept our artworks as collateral for our mortgage – even if art already has a huge emotional, aesthetic, intellectual, and social value for owners, art lovers, and laymen.

"Rainbow" pendant, Wagner Collection. Photo: Wagner Preziosen.

The Art Paradox

Even if an artwork does not have value, as argued earlier, it does have a price. And once an artwork has a price, it also acquires an economic and monetary value; it can be traded in auctions, it can be counted with other corporate assets, it can be insured against damage, it can be used to boost prestige and productivity by decorating a corporate lobby and thus enable new business by implying social and financial success.

Unlike the pair of shoes, the artwork has monetary value once the market has validated its trading price – and not vice versa. The ‘market’ means that a buyer is willing to purchase the artwork at the seller’s offering price.

What defines or influences the artwork's price?

1. Art prices exist only when an object is sold; thus, if you put a value of 100 euros on an artwork but sell it for 50, the price of the artwork is 50 euros.

2. At various moments of an artist's life, the price of the same artwork he or she created may equal the price of a loaf of bread or one year's wages of a laborer or the annual revenues of a corporation. For example, during his lifetime the modernist painter Amadeo Modigliani paid for his daily meal in a Parisian tavern with a drawing he made; his works today carry a price in nine digits.

3. The price of an artwork is influenced by the following factors: artist's excellence; difficulty level or uniqueness of techniques; scarcity of materials; reproducibility or uniqueness of the artwork; recognizability or fame of the artist; show reviews by the mainstream and specialized press; catalogues; exposure of the specific artwork via mass media / film / catalogue; acquisition of the artist's works by institutional, corporate, or private collections.; whether the artist is fashionable or ‘trending’; the artist's curriculum vitae, i.e., exhibitions in reputable venues, prizes, grants, scholarships; the artist's exposure through activism for good causes, politics, social issues; number of works available; the artist's ‘productivity;’ network of buyers willing to pay the asking price.

The price of an artwork has nothing to do with its aesthetic, philosophical, emotional, or social value. A high- or low-priced object in a specific society and era may receive a completely different financial evaluation years or centuries later.

Paul Gauguin used his art pay the grocer, who gave him credit with sketches on paper. The grocer did not think much of Gauguin and his art, and the only use he saw in these sketches was to wrap the sardines that he sold to other customers who paid him with money.

"The Curator Brooch" by Christoph Ziegler. Photo: Chr. Ziegler.

Tips for pricing your work

1. If you are new in the art market or a recent graduate, you can find your price spectrum by looking at the market performance of other artists of similar background or experience or recognizability or age – or all of these. You may find interesting examples and records in art sales, auctions, or gallery websites. Never forget: an artist's price has nothing to do with her or his “artistic value,” skills, ideas, sophistication, or merit; if your price is low now, you can make it grow!

2. If you calculate your art’s price by the working hours or the value of materials you use, you may arrive at wrong conclusions. Look at auction catalogues for references on how prices are set and how they change under different circumstances.

3. The good news is that you can influence the price of your artworks. Independent artists who look for opportunities to sell their work should channel their energy towards building a solid biography and aim at getting as much exposure as possible. Collect intelligence and insider information on deals, galleries, collectors; apply targeted promotion of your work to be seen by experts, journalists, and collectors; and, importantly, learn the rules of professional communication.

Homepage: www.loukiarichards.net

Instagram: @loukiarichards